Scattered notes on Digital Gardens

22 Settembre 2021 - #digitalgarden - Alessandro Y. Longo

As explained in the About section, the REINCANTAMENTO web space follows the concept of the Digital Garden in its development. In addition to inspiring the site, that digital garden is about the concept of re-enchantment itself: it is a model (however unfair it may be to call it such) that has the specific goal of bringing magic, fun, and exploration back into the web experience. Therefore, we could not help but delve into it. We do so with what cannot be called a true article but rather is intended to be a path through various hypertext sources and which we hope will provide useful cognitive resources.

Suggested listening: Arman Doley by Mamman Sani

Suggested listening: Arman Doley by Mamman Sani

The first approach to the idea of a digital garden came to me through this MIT article. According to the article, the oldest juxtaposition between a garden and a website dates back to the work of Mark Bernstein in 1997. Bernstein, at the time of the early Internet, was already talking about Hypertext Gardens, albeit in a different sense than we use today. In fact, Maggie Appleton's crucial story highlights:

“While the essay is a beautiful ode to free-wheeling internet exploration, it's less about building personal internet spaces, and more of a manifesto on user experience flows and content organisation.”.

Bernstein appreciates the garden as a middle ground between the wilderness of a forest and the anthropic environment of a farm. According to the author, it is precisely this openness to the Other, to the 'wild,' that can be useful in the process of hypertext construction. In this way, one avoids the disadvantages that the imposition of a rigid hypertext structure brings to the content (according to Bernstein's second gardening lesson):

“Rigid hypertext structure is costly. By repeatedly inviting readers to leave the hypertext, by concentrating attention and traffic on navigation centers, and by pushing content away from key pages (and traffic), rigid structure can hide a hypertext's message and distort its voice.”

“Rigid hypertext structure is costly. By repeatedly inviting readers to leave the hypertext, by concentrating attention and traffic on navigation centers, and by pushing content away from key pages (and traffic), rigid structure can hide a hypertext's message and distort its voice.”

These were typically 1990s concerns when people were still trying to find the ideal balance for designing an ideal Web page. But let us continue to follow Appleton in her history of gardens to arrive at the modern understanding of the term.

The next brick is an essay dating from 2015, ‘The Garden and the Stream: A Technopastoral’ by Mike Caufield. One comment immediately stands out: "The appeal here is in building complexity, not reducing it." The idea of creating pages that are balls of complexity and difference is crucial if you want to build something different from the simplifying and mundane world of social: to collect links, sources, studies, music, images, and videos in order to provide a prismatic representation of what you want to represent. If we think about it, the experience of visiting a well-done online page always coincides with the parallel opening of other tabs alongside the one visited; reading a long-form or an online interview is not the same thing as reading a book for this very reason: the drift to other links that online reading (and, more generally, browsing) allows is its specific and inimitable feature in non-hypertextual works. Undoubtedly, this experience of virtual walking through disparate links has an alternative potential to the compulsive scrolling that has made its way into the more commercial spaces of the Internet.

The next brick is an essay dating from 2015, ‘The Garden and the Stream: A Technopastoral’ by Mike Caufield. One comment immediately stands out: "The appeal here is in building complexity, not reducing it." The idea of creating pages that are balls of complexity and difference is crucial if you want to build something different from the simplifying and mundane world of social: to collect links, sources, studies, music, images, and videos in order to provide a prismatic representation of what you want to represent. If we think about it, the experience of visiting a well-done online page always coincides with the parallel opening of other tabs alongside the one visited; reading a long-form or an online interview is not the same thing as reading a book for this very reason: the drift to other links that online reading (and, more generally, browsing) allows is its specific and inimitable feature in non-hypertextual works. Undoubtedly, this experience of virtual walking through disparate links has an alternative potential to the compulsive scrolling that has made its way into the more commercial spaces of the Internet.

Describe ‘technopastoral’ in one picture

This old review in the Manifesto of a book by Alberto Donzelli, preserved in an online archive, reminds us of the fact that: "There is nothing more subversive, more alternative to the dominant way of thinking and acting today than walking" and that "walking is an extraordinary exercise of freedom."

Little does it matter if Donzelli opposed this walking to technology, the idea of the Digital Garden we are talking about is instead meant to include the power of walking through the constructs of technology such as Web pages. Caufield opposes the Garden precisely to the Flow, the continuous stream, by which social, online news, etc. function.

“The Garden is the web as topology. The web as space. It’s the integrative web, the iterative web, the web as an arrangement and rearrangement of things to one another.

Things in the Garden don’t collapse to a single set of relations or canonical sequence, and that’s part of what we mean when we say “the web as topology” or the “web as space”. Every walk through the garden creates new paths, new meanings, and when we add things to the garden we add them in a way that allows many future, unpredicted relationships”

On the other hand, the Stream:

“In the metaphor of flow, one does not experience the flow by walking around it and watching it, or following it to its end. You jump into it and let it flow. You feel its force hitting you as things float by. [...] It's not that you are passive in the flow. You can be active. But your actions in there -- your blog posts, @ mentions, forum comments -- exist in a context that is collapsed into a simple timeline of events that together form a narrative. In other words, the Stream replaces topology with serialization. Rather than imagining a timeless world of connection and multiple paths, the Stream presents us with a single time-ordered path with our experience (and only our experience) at the center. While the garden is integrative, the Stream is self-assertive. It is persuasion, it is argumentation, it is advocacy. It is personal, personalized and immediate. It is invigorating. And as we will see in a minute, it is also profoundly unsuitable for some of the uses to which we put it."

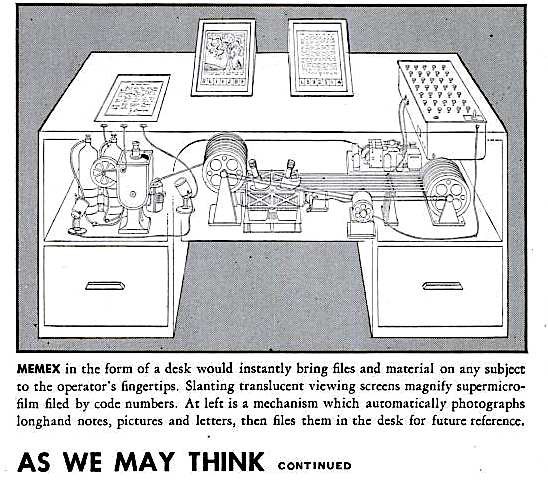

Caufield's Garden brings aback to life Vannevar Bush's original vision of the Memex, a machine envisioned in 1945 by the U.S. engineer in this article in The Atlantic, titled As We May Think. Bush imagines in many respects the modern computer but at the same time, and this is what Caufield notes, the conditional in the title is still a conditional: we do not yet think as we might think should we actually have implemented the hypertext machinery recounted by Bush.

“Wholly new forms of encyclopedias will appear, ready made with a mesh of associative trails running through them, ready to be dropped into the memex and there amplified. ”

For Bush we might come to reason through parallel and unexpected paths, inventing a new way of charting routes in our knowledge. Instead, we find ourselves in a situation diametrically opposite to that envisioned by Memex, as Caufield explains:

“So in 2006 or so Twitter, Facebook and other sites move to a model directly inspired by this personal page + feed reader combination. You have a page which represents you, in a reverse chronological stream — your Facebook page or Twitter home page.The pages of people you are friends with get aggregated into a serialized time ordered feed. Your Stream becomes your context and your interface.

And we see that develop into the web as we know it today. A web of “hey this is cool” one-hop links. A web where where links are used to create a conversational trail (a sort of “read this if you want to understand what I am riffing on” link) instead of associations of ideas. [...] The “Conversational Web”. The “conversational web”. A web obsessed with arguing points. A web seen as a tool for self-expression rather than a tool for thought. A web where you weld information and data into your arguments so that it can never be repurposed against you. The web not as a reconfigurable model of understanding but of sealed shut presentations. And a web that can be beautiful and still is beautiful on so many days. I can’t stress this enough. I’m not here to bury the Stream, I love the Stream. But it’s an incomplete experience, and it’s time we fixed that.”

Caufield then stresses the importance of learning how to use tools in order to actually build your own gardens. This is a central point. The idea of 'getting your hands dirty,' of disseminating knowledge of what I have called digital craftsmanship, and which consists of a (potentially infinite) set of skills - writing, design, code etc. - also has a certain political value. I am convinced that only through a dissemination of knowledge and technical skills can the monopoly of the online giants be challenged. I am convinced that without adequate technical awareness and consciousness, few people will be able to adopt (and build) the software and hardware alternatives to corporate dominance and that they already exist, as Giulio Quarta points out:

But back to our gardens. Another principle (assuming that we can talk about principles in the first place) of digital gardens is that "curation comes before chronological order," to use the words of Joel Hooks, digital gardener and author of this very clearly titled post. Hooks explains that:

"Chronologically sorted pages of posts aren't how people actually use the internet. For the most part we use search via Google to find stuff, which is free form and task oriented. You want something, you know what you want, you can string a few words together and hope to get lucky.."

Hooks' words force me to reflect on the architecture of my garden. In its construction in fact, I did not totally follow this principle because I felt that chronology could still be an effective method of structuring content. However, when you find two keys flowing under an article you can follow a recommended reading path, which connects together articles written in different periods and published in different corners of the Web. It seems to me that in building a digital garden it is difficult to find the right balance between chaos and order, between 'magical' association and aesthetics and pure functionality or, to put it another way, between wild forest and man-made environment. In a garden: "Things are organized and orderly, but with a touch of chaos around the edges."

In the case of the site you are visiting, the wildest part is definitely the Garden, so-called because it is the actual place where seeds and cues are sown almost daily, especially of a visual nature (but also quotes, videos, poems etc.).

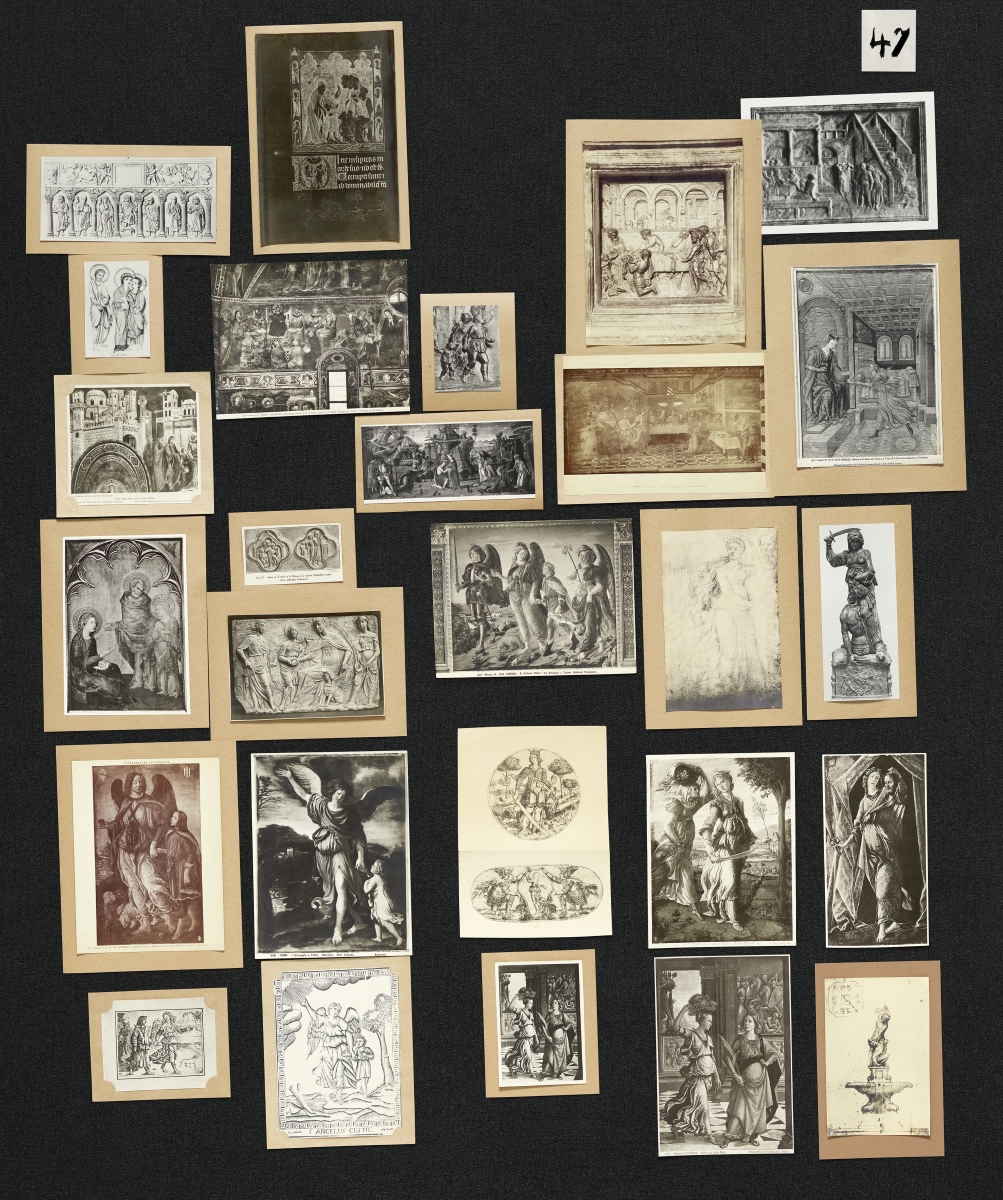

Philosophically, I have always believed in the potentiality of chaos and, at the same time, I think that through the practice of juxtaposition and analogy one can also develop something more accomplished, a 'thought' in the proper sense'. For this, the Garden is also deeply indebted to Aby Warburg's Mnemosyne Atlas, a table of images (Bilderatlas) structured by the German art critic to study the fate of forms and other visual components through human history. Warburg juxtaposed advertisements and newspaper clippings with Renaissance painting classics and much more, as Engramma, a fundamental resource for Warburghians, explains. Warburg's work has also been taken up by the Clusterduck collective (whose official website is fully a digital garden) in the creation of their Meme Manifesto, a total study of the memetic production of our times.

![]()

![]()

![]()

In addition to this conceptual inspiration, a more direct influence comes from the aesthetics of Tumblr blogs, which, at the turn of the 00s and 10s, offered a space of freedom and expression to their users that was very different from Twitter and Facebook. A freedom that came primarily from the ability to freely edit the code of one's blog, making one's personal page a space on which to act and not a static black box.

"Chronologically sorted pages of posts aren't how people actually use the internet. For the most part we use search via Google to find stuff, which is free form and task oriented. You want something, you know what you want, you can string a few words together and hope to get lucky.."

Hooks' words force me to reflect on the architecture of my garden. In its construction in fact, I did not totally follow this principle because I felt that chronology could still be an effective method of structuring content. However, when you find two keys flowing under an article you can follow a recommended reading path, which connects together articles written in different periods and published in different corners of the Web. It seems to me that in building a digital garden it is difficult to find the right balance between chaos and order, between 'magical' association and aesthetics and pure functionality or, to put it another way, between wild forest and man-made environment. In a garden: "Things are organized and orderly, but with a touch of chaos around the edges."

In the case of the site you are visiting, the wildest part is definitely the Garden, so-called because it is the actual place where seeds and cues are sown almost daily, especially of a visual nature (but also quotes, videos, poems etc.).

Philosophically, I have always believed in the potentiality of chaos and, at the same time, I think that through the practice of juxtaposition and analogy one can also develop something more accomplished, a 'thought' in the proper sense'. For this, the Garden is also deeply indebted to Aby Warburg's Mnemosyne Atlas, a table of images (Bilderatlas) structured by the German art critic to study the fate of forms and other visual components through human history. Warburg juxtaposed advertisements and newspaper clippings with Renaissance painting classics and much more, as Engramma, a fundamental resource for Warburghians, explains. Warburg's work has also been taken up by the Clusterduck collective (whose official website is fully a digital garden) in the creation of their Meme Manifesto, a total study of the memetic production of our times.

In addition to this conceptual inspiration, a more direct influence comes from the aesthetics of Tumblr blogs, which, at the turn of the 00s and 10s, offered a space of freedom and expression to their users that was very different from Twitter and Facebook. A freedom that came primarily from the ability to freely edit the code of one's blog, making one's personal page a space on which to act and not a static black box.

The last digital garden-themed text I want to address is Digital Garden Terms of Service. There is a passage in this writing that explains in no uncertain terms what my idea has been from the beginning with REINCANTAMENTO:

“A Digital Garden is your very own place (often a blog, or twitter account) to plant incomplete thoughts and disorganized notes in public - the idea being that these are evergreen things that grow as your learning does, warmed by constant attention and fueled by the unambiguous daylight of peer review.”

This 'ethic of incompleteness,' which is expressed in a tendency to publish work-in-progress, must be accompanied by constant criticism from the 'public.' According to the article, such critique should be strongly encouraged and demanded, as if to show how (fiercely) incomplete, fragile and unperfect This is another difference with social, where it seems to me instead that etiquette always dictates that one should show oneself very confident and proud of one's work, in an environment of constant performativity and competition. To the progressive professionalization of being on the Internet, the digital garden responds with a mixed attitude that combines what is "intimate" with what is "public," a "strange" component with a familiar and welcoming one. If social media led to uniformity and the adoption of a unique and always recognizable voice, gardens are children of hybridization and heterogeneity. We like to think of gardens as therapy, an attempt to cure some of the toxic dynamics of the online world by changing our relationship with the digital medium. Gilles Clément’s words, quoted by Italian philosopher Tommaso Guariento in his history of gardens, that sum up the ethos and potential of gardening:

"The natural therapy of gardening comes from suspended time, from time that one does not master and that, indeed, in a certain way is what holds us up. When you put a seed in the ground, with it is a becoming that is announced, while the past is erased; nostalgia has no meaning in the garden. The garden is a privileged place of the future, a natural territory of hope."

We can only hope then that a thousand digital gardens may arise and occupy the horizon of tomorrow's Web.

Resources for digital gardening

- - https://www.technologyreview.com/2020/09/03/1007716/digital-gardens-let-you-cultivate-your-own-little-bit-of-the-internet/?utm_source=pocket_mylist

-

- http://www.eastgate.com/garden/Seven_Lessons.html

-

- https://maggieappleton.com/garden-history?utm_source=pocket_mylist

-

- https://www.donzelli.it/reviews/1465

-

- https://www.theatlantic.com/magazine/archive/1945/07/as-we-may-think/303881/

-

- https://joelhooks.com/digital-garden

- - https://www.swyx.io/digital-garden-tos/