Utopia, Alchemy, Post-Scarcity

27 Gennaio 2021 - #Alchemy #utopia #psychedelia - Alessandro Y. Longo -

“He walks the streets on winter nights, without a home,

without clothes, without bread; and he wants gold.”

Pier Paolo Pasolini, La divina Mimesis

without clothes, without bread; and he wants gold.”

Pier Paolo Pasolini, La divina Mimesis

In the book Alchemy and Utopia, the great heretical thinker Luciano Parinetto draws a line between the practices of alchemists and the desire for a better world: alchemical research fueled an imagination of hope and future, which, over centuries, found expression in revolutionary thought and the labor movement. In this sense, alchemy is one of the “alternative” roots of the struggle for emancipation, as described by Erica Lagalisse in Occult Features of Anarchism, recently published in Italian. This issue of Speculum, dedicated to utopia, seemed to us the ideal (non)-place for an archaeology of this millennial discipline.

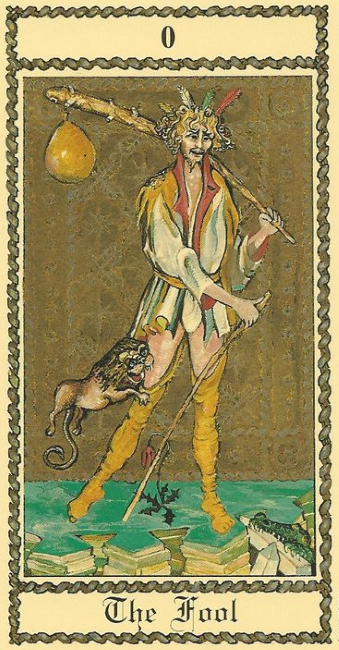

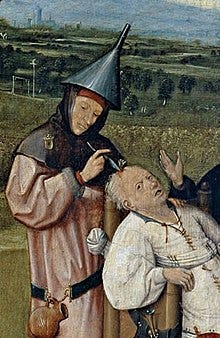

Although it is an ancient art, alchemy became widely known and discussed in Europe only from the 14th century onwards until about the 19th century. It was a "trend" that affected all European countries and crossed all social classes. However, alchemy was not viewed kindly and was often associated with madness: “Abbots, bishops, doctors, hermits [...] all dealt with it; it was the madness of the day, and every century has its own” (quoted by Parinetto). There is an analogy, masterfully highlighted by Parinetto, between the representation of the “mad” and the denigratory portrayal of alchemists, to the point where some identified the “stone of madness”—the root of mental illness according to the wisdom of the time—with the Philosopher's Stone sought by alchemists. This is also evident in the Tarot card number 0, "The Fool," also called the Alchemist.

Fools, thieves, devil worshippers, counterfeiters (according to Dante’s Inferno): these are some of the accusations that alchemists faced throughout the centuries, which often relegated them to social marginality (with some exceptions). Parinetto recounts a Greek myth—brought to us by Paracelsus—about the origin of alchemy, which seems to summarize all the negative connotations associated with the discipline:

"Some angels fell in love with women. They descended to earth and taught them the operations of nature. It is of them that the Bible said those who became proud were cast out of heaven, because they had taught men everything evil, useless to the soul. It is they who composed the works, and from them comes the first tradition of these arts. Their book is called Koumou, and it is from this that the word 'Koumia' derives."

Fallen angels seduced by the feminine: the devil and the feminine converge to give birth to a malevolent discipline that aims to manipulate Nature. Parinetto’s coup de théâtre is to reverse the common perception of alchemists, these forgotten ones from history, decapitated by the sword of the Church first, and by that of the Enlightenment later. Like the witches of Silvia Federici, Parinetto's alchemists are closer than ever to our struggles for freedom and emancipation, sui generis pioneers of Marxist utopias and science fiction.

Fools, thieves, devil worshippers, counterfeiters (according to Dante’s Inferno): these are some of the accusations that alchemists faced throughout the centuries, which often relegated them to social marginality (with some exceptions). Parinetto recounts a Greek myth—brought to us by Paracelsus—about the origin of alchemy, which seems to summarize all the negative connotations associated with the discipline:

"Some angels fell in love with women. They descended to earth and taught them the operations of nature. It is of them that the Bible said those who became proud were cast out of heaven, because they had taught men everything evil, useless to the soul. It is they who composed the works, and from them comes the first tradition of these arts. Their book is called Koumou, and it is from this that the word 'Koumia' derives."

Fallen angels seduced by the feminine: the devil and the feminine converge to give birth to a malevolent discipline that aims to manipulate Nature. Parinetto’s coup de théâtre is to reverse the common perception of alchemists, these forgotten ones from history, decapitated by the sword of the Church first, and by that of the Enlightenment later. Like the witches of Silvia Federici, Parinetto's alchemists are closer than ever to our struggles for freedom and emancipation, sui generis pioneers of Marxist utopias and science fiction.

What do alchemists dream of?

The alchemical utopia is a Promethean utopia that seeks to establish a transformative relationship with nature and matter to ultimately transform the alchemist himself. A practical and cognitive process that aims to unleash the tension present in matter to release an energy of liberation: "For matter also suffers, struggles, and aspires, like us, towards perfection and cries: Help me, and I will help you; free me, and I will free you" (Alleau, Aspects).

Alchemy, like Gnosis or psychedelia, seeks to bring man to a new level of "enlightenment," which can only be reached through hard practice and a certain isolation. In a way, alchemists were indeed 'marginalized,' not only for social reasons but due to the transmutative process they subjected themselves to.

It is clear that in Europe, this clashed with the established authority par excellence: the Church. In this clash, to the terrible accusations made against them, alchemists responded with the strength of dissent that would characterize many later movements. Parinetto emphasizes how alchemy often, and I would add, courageously, uses Christian metaphors but adapts them to its own language: for example, Christ, for those familiar with the hermetic and secret codes of alchemy, represents the element of mercury. The reversal of Christianity is central to all of alchemy, which arches towards a utopian desire that would later be taken up by revolutionary movements: to realize the kingdom of heaven on earth, to free bodies and minds now, without waiting for a transcendent goal.

Another example of reversal is in how the idea of incest (on a symbolic level) is treated. In an important alchemical text like The Twelve Keys of Basil Valentine, the Greek myth of Orpheus and Eurydice is retold with a variation: the two are brother and sister and are unable to have children. Orpheus is visited by Phoebus, a winged messenger, who offers him a solution to his problem: he must mix his own blood and that of his spouse with the blood of the heart of his father and mother, and blend it all in the globe of the seven sages, thus achieving the birth of a ‘new son, three times great.’ By repeating the operation many times, Orpheus’s lineage will multiply infinitely, gaining wealth and power, until they come to ‘possess the celestial kingdom of the creator of the universe.’

Several elements are at play here. First, incest—condemned at the core of Christian morality—is presented as something positive and brimming with possibility, generating power and wealth. The promise made by Phoebus blasphemously mirrors the covenant between Yahweh and Abraham (whose name in Hebrew means ‘father of many’), which would give rise to his descendants. However, this time we are witnessing an act of human affirmation, through alchemical operation, that brings fertility and prosperity through the mixing of incestuous blood. Incest, which is seen in the Christian world as one of the first barriers between what is ‘natural’ and what falls on the other side of the line, into unnaturalness and thus, sin, is instead, for alchemists, part of the totality of existence, with nothing that exists falling outside the realm of nature. Alchemy recalls the ontology of Baruch Spinoza, for whom everything that exists is natural, and nothing can truly happen outside this idea.

Finally, this reversal of Orpheus and Eurydice is another way of narrating one of the most important ideas in the alchemical tradition: the creation of the homunculus, a product of this generative incest. This concept, again tracing back to Paracelsus, is the idea of creating a man in a test tube, through the power of alchemical operations. The creative will of the alchemists already stands as an affront to the monotheistic God, who holds the monopoly on the generation of new lives. Beyond being a theme that humanity has faced and will continue to face in the centuries to come (cloning, in-vitro births, etc.), the alchemists’ new artificial child (though still within the realm of nature) will be ‘thrice great,’ and thus even superior to God's creation, which is man itself, ultimately ‘conquering’ the celestial kingdom. Humanity wins the challenge against God thanks to its poietic capacity: this is a full-fledged transmutation of values, one that precedes by several centuries Nietzsche’s announcement of the death of God or the utopia of the Constructors of God by Lunacharsky, and which fuels revolutionary dreams that would torment society in the following eras.

Alchemy, like Gnosis or psychedelia, seeks to bring man to a new level of "enlightenment," which can only be reached through hard practice and a certain isolation. In a way, alchemists were indeed 'marginalized,' not only for social reasons but due to the transmutative process they subjected themselves to.

It is clear that in Europe, this clashed with the established authority par excellence: the Church. In this clash, to the terrible accusations made against them, alchemists responded with the strength of dissent that would characterize many later movements. Parinetto emphasizes how alchemy often, and I would add, courageously, uses Christian metaphors but adapts them to its own language: for example, Christ, for those familiar with the hermetic and secret codes of alchemy, represents the element of mercury. The reversal of Christianity is central to all of alchemy, which arches towards a utopian desire that would later be taken up by revolutionary movements: to realize the kingdom of heaven on earth, to free bodies and minds now, without waiting for a transcendent goal.

Another example of reversal is in how the idea of incest (on a symbolic level) is treated. In an important alchemical text like The Twelve Keys of Basil Valentine, the Greek myth of Orpheus and Eurydice is retold with a variation: the two are brother and sister and are unable to have children. Orpheus is visited by Phoebus, a winged messenger, who offers him a solution to his problem: he must mix his own blood and that of his spouse with the blood of the heart of his father and mother, and blend it all in the globe of the seven sages, thus achieving the birth of a ‘new son, three times great.’ By repeating the operation many times, Orpheus’s lineage will multiply infinitely, gaining wealth and power, until they come to ‘possess the celestial kingdom of the creator of the universe.’

Several elements are at play here. First, incest—condemned at the core of Christian morality—is presented as something positive and brimming with possibility, generating power and wealth. The promise made by Phoebus blasphemously mirrors the covenant between Yahweh and Abraham (whose name in Hebrew means ‘father of many’), which would give rise to his descendants. However, this time we are witnessing an act of human affirmation, through alchemical operation, that brings fertility and prosperity through the mixing of incestuous blood. Incest, which is seen in the Christian world as one of the first barriers between what is ‘natural’ and what falls on the other side of the line, into unnaturalness and thus, sin, is instead, for alchemists, part of the totality of existence, with nothing that exists falling outside the realm of nature. Alchemy recalls the ontology of Baruch Spinoza, for whom everything that exists is natural, and nothing can truly happen outside this idea.

Finally, this reversal of Orpheus and Eurydice is another way of narrating one of the most important ideas in the alchemical tradition: the creation of the homunculus, a product of this generative incest. This concept, again tracing back to Paracelsus, is the idea of creating a man in a test tube, through the power of alchemical operations. The creative will of the alchemists already stands as an affront to the monotheistic God, who holds the monopoly on the generation of new lives. Beyond being a theme that humanity has faced and will continue to face in the centuries to come (cloning, in-vitro births, etc.), the alchemists’ new artificial child (though still within the realm of nature) will be ‘thrice great,’ and thus even superior to God's creation, which is man itself, ultimately ‘conquering’ the celestial kingdom. Humanity wins the challenge against God thanks to its poietic capacity: this is a full-fledged transmutation of values, one that precedes by several centuries Nietzsche’s announcement of the death of God or the utopia of the Constructors of God by Lunacharsky, and which fuels revolutionary dreams that would torment society in the following eras.

As Michela Pereira explains in Arcana Sapienza:

‘The secret of alchemy does not reside in content that can be objectified [...] The "secret of the secret" is the idea that the incorruptibility and immortality that humanity aspires to, which religious traditions place in the transcendental world (in the "afterlife"), can be produced through human labor in this body, in this world.’

Alchemists, to quote Nanni Balestrini, wanted everything, and their work, the completion of the Opus, was a centuries-long process that developed alternative ideas to those in power. For this reason, alchemy is compared by Luciano Parinetto to Marx's mole, invoked in a famous passage by the German philosopher, representing revolution: not a mighty animal that faces its enemies in the open field, but a patient creature that digs tirelessly toward its goal, until the day it will emerge on the surface.

‘The secret of alchemy does not reside in content that can be objectified [...] The "secret of the secret" is the idea that the incorruptibility and immortality that humanity aspires to, which religious traditions place in the transcendental world (in the "afterlife"), can be produced through human labor in this body, in this world.’

Alchemists, to quote Nanni Balestrini, wanted everything, and their work, the completion of the Opus, was a centuries-long process that developed alternative ideas to those in power. For this reason, alchemy is compared by Luciano Parinetto to Marx's mole, invoked in a famous passage by the German philosopher, representing revolution: not a mighty animal that faces its enemies in the open field, but a patient creature that digs tirelessly toward its goal, until the day it will emerge on the surface.

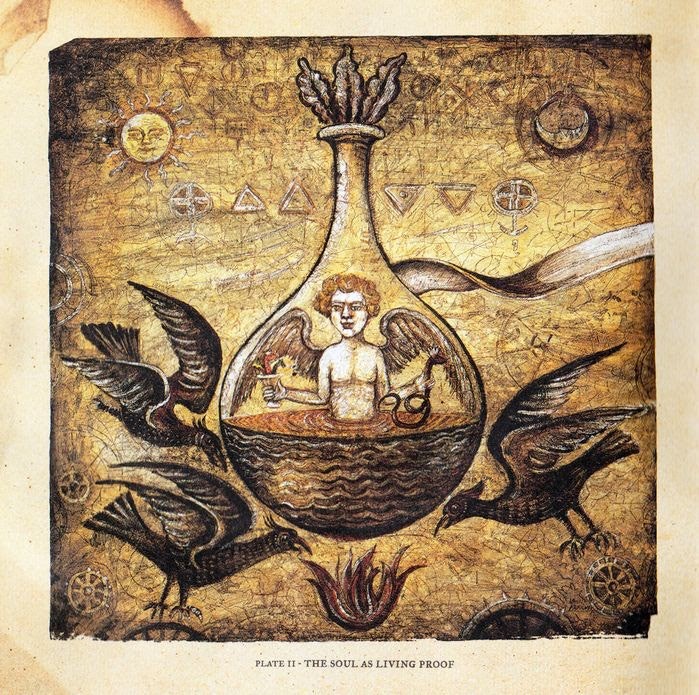

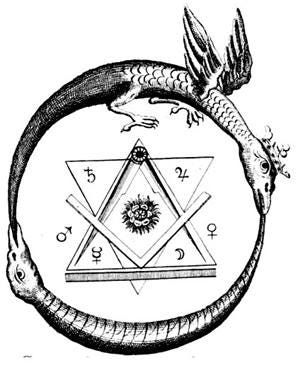

The Rebis - Power of the Hermetic Androgyne

The Rebis is a typical figure of alchemical iconography: an androgynous symbol that unites man and woman in a coincidentia oppositorum that transcends dual oppositions. The Rebis is an emblem of the alchemical Work, the overcoming of unilateral differences in a celebration of the unity of matter. This happens through the union of the two sexes because alchemical matter is considered living matter, a proliferation of energetic and libidinal flows: alchemy recognizes the importance of themes like sex and desire. The Rebis celebrates the endless potential of nature, which never exhausts itself. It is said that the Rebis is the child of the Ouroboros, the serpent that impregnates itself: yet another revaluation of an act considered unnatural, here celebrated as a giver of life.

For this reason, alchemy has been studied by several psychoanalysts in the 20th century, from Carl Jung onward: the alchemical discipline is already an early attempt to address themes of the unconscious and sexual development. The Rebis expresses the protean power of alchemical concepts, capable of dissolving oppositions and truly visualizing a new man, starting from his formation. Alchemy’s ontological hope is based on a vitalistic conception of matter, seen as a boiling humus full of possibilities, associated with Lucifer rather than God, the symbol of celestial immobility. Thus, the philosopher’s stone, the culmination of the alchemical process, is considered by Jung to be ‘the concretization, a materialization that touches the lower plane of the darkest, inorganic realm of matter, if not emerging from it.’ The Stone was often represented through a perfect and androgynous living figure (the Homunculus mentioned above), father and mother of a lineage of future (super)men.

Anticipating Zarathustra once again, alchemy redeems the Earth. Nietzsche wrote: ‘Remain true to the earth, my brothers, with the power of your virtue! May your giving love and your knowledge serve the meaning of the earth. Thus I implore and beseech you. Do not let it fly away from earthly things and crash with its wings against eternal walls!’ A passage that resonates with the alchemical classic Chimico crivello by Parafraste Ocella, quoted by Parinetto: ‘The earth (...) we well know it to be the only one never to get angry with Man; always, rather, to gratify him’ (pg. 337-9). Another connection: Nietzsche called his Zarathustra a "philosopher's stone." Alchemy expresses a form of love for the material and earthly life of man: whereas Christ preached the separation of earthly and heavenly life, the alchemist instead seeks acceptance and affirmation of both earth and sky.

The true life of matter can only be grasped by getting one’s hands dirty with it: true work poetry, alchemy seeks to transcend the division between theory and practice, in a flash of ante-litteram Marxism: ‘Alchemical science cannot be taught; each must learn it for themselves, not in a speculative way, but with the help of persevering work [...] Whoever fears manual labor, the heat of the ovens, the dust of coal [...] will never know anything’ (Fulcanelli, Les Demeures).

Alchemy is a praxis, and without praxis, it risks remaining a dead letter: only through commitment and effort in labor can we overcome the alienated life of the present.

Parinetto records the use of the term alienation in alchemical language (‘alienati sumus’ is said in the Crater Hermetis), which may have influenced philosophers who later worked on this concept—Rousseau, Hegel, Marx. Man is said to be ‘alienated’ when rejected by natural harmony, but ‘to alienate’ is also a technical term in alchemy to indicate transmutation: in this overdetermination of meanings, the idea of alienation begins to take on the ambiguous form it would later hold in Enlightenment and Marxist philosophy: ‘to become other in a positive sense (transmutation/transformation for the better) and to become other in a worsening sense, precisely in a state of alienation’.

Anticipating Zarathustra once again, alchemy redeems the Earth. Nietzsche wrote: ‘Remain true to the earth, my brothers, with the power of your virtue! May your giving love and your knowledge serve the meaning of the earth. Thus I implore and beseech you. Do not let it fly away from earthly things and crash with its wings against eternal walls!’ A passage that resonates with the alchemical classic Chimico crivello by Parafraste Ocella, quoted by Parinetto: ‘The earth (...) we well know it to be the only one never to get angry with Man; always, rather, to gratify him’ (pg. 337-9). Another connection: Nietzsche called his Zarathustra a "philosopher's stone." Alchemy expresses a form of love for the material and earthly life of man: whereas Christ preached the separation of earthly and heavenly life, the alchemist instead seeks acceptance and affirmation of both earth and sky.

The true life of matter can only be grasped by getting one’s hands dirty with it: true work poetry, alchemy seeks to transcend the division between theory and practice, in a flash of ante-litteram Marxism: ‘Alchemical science cannot be taught; each must learn it for themselves, not in a speculative way, but with the help of persevering work [...] Whoever fears manual labor, the heat of the ovens, the dust of coal [...] will never know anything’ (Fulcanelli, Les Demeures).

Alchemy is a praxis, and without praxis, it risks remaining a dead letter: only through commitment and effort in labor can we overcome the alienated life of the present.

Parinetto records the use of the term alienation in alchemical language (‘alienati sumus’ is said in the Crater Hermetis), which may have influenced philosophers who later worked on this concept—Rousseau, Hegel, Marx. Man is said to be ‘alienated’ when rejected by natural harmony, but ‘to alienate’ is also a technical term in alchemy to indicate transmutation: in this overdetermination of meanings, the idea of alienation begins to take on the ambiguous form it would later hold in Enlightenment and Marxist philosophy: ‘to become other in a positive sense (transmutation/transformation for the better) and to become other in a worsening sense, precisely in a state of alienation’.

The alchemists’ utopia is a Promethean utopia, one that exalts man’s powers to shape reality as he pleases. Prometheus is perhaps the first alchemist in history because, according to Aeschylus, he was the discoverer of metals like iron and gold, as well as the quintessential technological experimenter.

Yet we should not consider alchemy a desire to dominate the external world: alchemy, in fact, has an ecological character we might recognize today. In the future, the whole of nature, not just man, will be redeemed. The alchemist will create a new earth and a new sky, as God once did, but he will do so in harmony with the cosmos, which he has grasped through his studies of symbols and analogies. Alchemy is deeply aware of the constant becoming that runs through the natural world, continuously changing and boiling with active processes. Parinetto approaches the texts of Ernst Bloch on utopia as a key to interpreting certain aspects of the alchemical utopia. Bloch saw a cosmos still in flux, confronted with the opportunity of alchemy: ‘Possibility is not yet exhausted. Possibility is a singular category of the gigantic laboratory that is the world, the laboratory of a possible salvation, a most tormented laboratorium possibilis salutis’ (Bloch, Marxism and Utopia). Nature is seen as an unfinished process, which can offer joy and prosperity to men if understood in its free, vital, and non-mechanical dimension.

The alchemical utopia holds an imaginative value for us, a “sketch, something open and not entirely circumscribable,” that fueled daydreams and hopes for the future throughout many centuries of medieval and Renaissance civilization. Throughout this period, alchemical language was part of every reformist and revolutionary project: the Rosicrucians, the Anabaptists, the mysticism of Meister Eckhart were all influenced by alchemical codes and the idea of spiritual and material regeneration. And again, Ernst Bloch saw alchemy as the root of the Enlightenment: in the hermetic secret societies of England and Germany, where higher alchemy was taught, the utopian ideas of universal equality and freedom were developed. The alchemical corpus particularly focuses on themes of equality and wealth distribution, to the point that it seems to prefigure, remaining within the utopian theme, the ideas of the post-scarcity society movement.

A world in which the production of goods and information is so abundant and requires so little effort that these goods become economically viable, if not free. A future scenario reminiscent of the alchemical dream of the philosopher’s stone, and which, like the work of alchemists, centers on the issue of distribution. The De Secretis Naturae, an important alchemical text attributed to Villanova, says: ‘Only by giving to the poor what he obtains with his God-guided technique can the alchemist achieve his own spiritual fullness in art.’ And there are many other similar quotations in the alchemical corpus.

Alchemy as a proto-utopia, as a “reformist Weltanschauung”, spread its seeds throughout Europe: seeds from which the revolutions and reforms of subsequent centuries would grow. Luciano Parinetto’s book is an invitation to “look at the mythologies that inhabit us,” successfully rehabilitating the forgotten and disparaged image of alchemy as a fundamental and pulsating root of revolutionary movements and their utopias. A discipline that, more than anything, produced hope—Luciferian in the truest sense of the word—for keeping Promethean fire burning through humanity’s longest nights. Nigredo est albedinis principium.